Research questions serve to guide your work and clearly identify the research gap in the field. They should be framed in such a way that the answer is not immediately obvious. True research involves exploring and understanding a system from a perspective that hasn’t been examined before.

If you are going into research seeking to prove some opinion or intuition of yours, that’s not genuine research. While your intuition can inspire intriguing research problems, the research itself – and the associated questions – should be constructed to avoid being biased toward confirming preexisting beliefs.

Pre-Requisites to Writing A Good Research Question

You need to read a lot about the field. This reading serves multiple purposes. First, reading a lot about the field improves your understanding of the field. As you read more papers, you’ll gain a clearer picture of the field’s current state. This understanding manifests in two ways: you will understand the broad classes of problems that interest others in the field and you will become familiar with the universities, institutions, and researchers actively working on those problems. Knowing who else is engaged in this area is valuable, as it can lead you to discover additional relevant papers, potential collaborators. It can even help you find a job because you can identify which companies are paying students/universities to study these problems.

The next purpose behind reading a lot is for you to understand what specific problems have not been solved before. In a master’s thesis or a PhD, you will not independently solve a huge problem like in-space assembly. These problems require massive teams of people to working together to address complex engineering challenges. As you read more about the field, more specific problems within a broader class should become apparent. The table below shows some examples of the differences between a broadly defined problem and a more specific problem.

| Broadly Defined Problem | Specific Problem |

| In-Space Assembly | Any construction process in the space environment will be constrained by the capabilities of the spacecraft, particularly its power budget and manufacturing efficiency. Low-power manufacturing methods are needed to allow for rapid fabrication of support structures |

| Delays in Air Traffic Management | Due to the concentration of air traffic volumes in the vicinityof large airports, inefficient aircraft maneuvers on arrival or departure often arise due to the need to maintain separation. |

The third purpose behind reading a lot is for you to understand what methodologies have been used before. It is highly likely the specific problem you’ve identified has some existing solution to it. For many new researchers, there’s a tendency to (1) stop when you’ve found a specific problem, thus performing a very shallow literature review, (2) get sad and give up entirely once you’ve read someone who “had” your idea for the method you wanted to use, or (3) pretend you didn’t read that paper and hope that nobody will call your bluff that a technique exists. But generating ideas and discovering that similar work already exists is a valuable part of the research process.

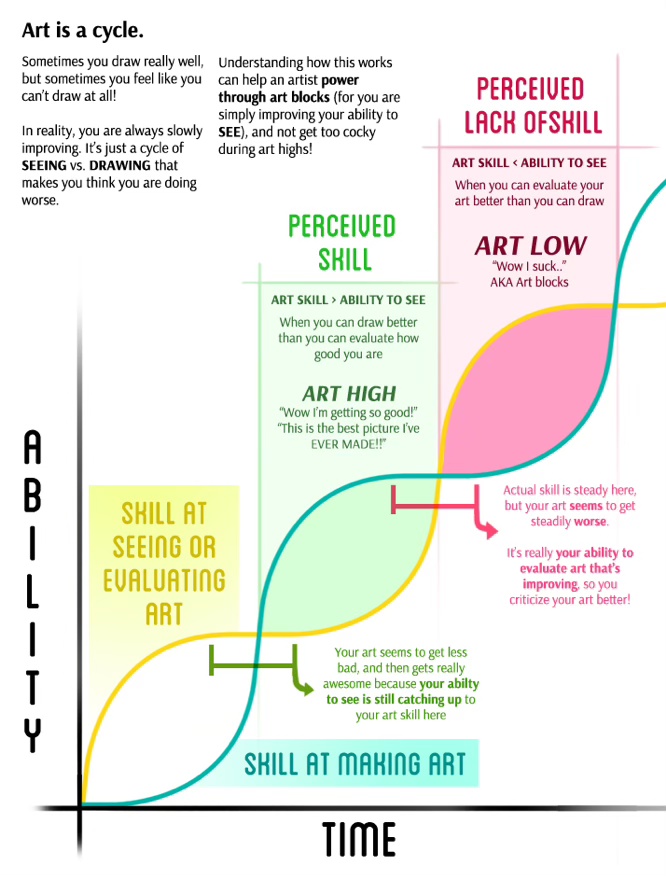

The figure below illustrates the “ability curve” commonly discussed in art communities, which highlights the tradeoff between the skill of creating art and the skill of evaluating it. Research follows a similar pattern. At times, you’ll excel at conducting research, while at others, you may feel dissatisfied with your work as your ability to critically evaluate it improves. Developing the skill to identify quality research and its relevance to your field (yellow curve) is as crucial as conducting the research itself (teal curve). Over time, these evaluation skills enhance the overall quality of your work.

Another point to consider when someone has “scooped” your idea, is that it doesn’t mean you can’t pursue it too. This is where a well-defined research question helps clarify your unique contribution. Focus on addressing specific figures of merit or problem classes, evaluating whether existing methods are sufficient and, if not, why. It’s perfectly fine to work on similar problems or use similar methodologies, as long as your research questions justify why your work remains valuable and necessary.

Tools for Finding Papers and Cataloguing all Your Reading

At MIT, a PhD thesis bibliography typically has more than 100 citations. And that’s just papers that are useful enough to be cited in the final thesis document! The process of writing a thesis will require you to read dozens of papers. Finding and then appropriately storing the papers you have read, is very important. Some recommended software to use in this process are:

- Zotero – open access tool that allows you to save references from library catalogues, research databases, and the web. You can annotate the documents you save and quickly create comprehensive bibliographies in most major citation styles. You can also create shared folders of all your citations, which is useful if you are working in teams.

- Mendeley – a reference manager tool used to manage citations. You can organize, annotate, and highlight PDFs, add to your citations, organize them into collections for different projects, and create bibliographies in Word.

Translating Understanding to Questions

Hopefully, you have done a sufficient amount of reading at this point, and you are now looking to define a research question. Now I would like to discuss qualities of a well-formed research question.

Specific – The question should address a specific problem. This problem should be narrow enough that readers of the research question should be able to easily visualize either the methodology in the question, or the application that the research question seeks to address. Furthermore, when you introduce your work later on, the research question needs to be narrow enough that it could only explain your work. If it could be applied to other students, you have not defined the problem in a detailed enough manner.

Attainable – The question should be written in such a way that it will be possible to get an answer. However, your research question should not be answered with a straightforward yes/no. The age-old answer you will get from any PhD is “it depends” but your research questions should be formed in such a way that the you can still provide some supplemental details or characteristics in the answer to the research question.

Useful – Readers of your question should understand why this sort of work would be valuable to pursue. This might not need to be explicitly stated, and can be potentially answered implicitly by the other qualities (i.e. specific, attainable). You should be able to read your own research question, and recognize the purpose and value that research serves.

Now, let’s go through a few examples of good and bad research questions.

Example 1:

| Bad | What are the primary challenges in designing space exploration missions? |

Why This Is Not Effective – This question is too broad. It also has decent answers available with a quick Google search. The simple version of this question can be looked up online and answered in a few factual sentences; it leaves no room for analysis. As a general rule of thumb, if a quick Google search can answer a research question, it’s likely not very effective. More details are needed to really define what research is actually being done here.

| Good | What are the key challenges faced during the development of exoplanet exploration missions, and how can tradespace analysis help optimize mission designs to meet specific science requirements and program constraints? |

What This Alternative Does Better – This alternative research question implicitly answers the “so-what”/significance. It connects how tradespace analysis will be used to inform specific science requirements and mission constraints, which helps readers understand the implications and value of this work.

Example 2:

| Bad | How will satellites guarantee global connectivity? |

Why This Is Not Effective – This research question is too narrowly framed and is steered to a specific type of answer. The way it is written designates satellites as the best solution to tele-communications connectivity, neglecting to consider current processes and infrastructure available. It is also assumed that satellites will be able to provide global connectivity, which was not known.

| Good | What kind of novel space and aerial systems can complement existing infrastructure and contribute towards expanding global connectivity at an affordable cost? What is the potential impact of such systems in terms of connecting additional populations? |

What This Alternative Does Better – This alternative research question accounts for a broader range of solutions to provide global connectivity (e.g. space and aeriel systems). It also asks an open-ended question about the nature of connectivity itself, rather than assuming that global connectivity is guaranteed.

Exercises That May Help You Write a Research Question

If you are still stuck with writing a research question, below are a list of possible questions and exercises to help you identify your question.

- Find a partner in your field. Read your proposed research question out loud to them, and ask them what their impression of the work you will do is. Do they have a good idea of the problem you are trying to address? Do they understand why this work would be valuable? If not, use their feedback to hopefully revise the research question to improve the clarity.

- Go through and ask yourself the following questions:

- How are current methods for this problem in my field done, and what are their limitations?

- After reviewing sources, what do you see as the latest problems in field of your topic?

Leave a comment